PRESIDENT’S DAY TUTORIAL—WHEN PRESIDENT WASHINGTON CONTROVERSIALLY “DECLARED” PEACE AND NEUTRALITY AND DEFINED EXECUTIVE AUTHORITY FOR HISTORY

INTRODUCTION

In the crucible of the Constitutional Convention, there was significant debate over the scope and definition of the executive branch. Ideas included designating in the Constitution a group of executives, which would have the vested executive authority in the separation of powers design of the new Republic. The Founders settled on a single “President of the United States.” Such an office would be subject to the political accountability of the vote and the impeachment powers of the Article I legislative branch. He would be elected by “electors” chosen by the people in elections held for the office in the states. Importantly, the vesting of the authority of this office was set forth in Article II, Section I, which in its text includes the following:

“…the executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America”

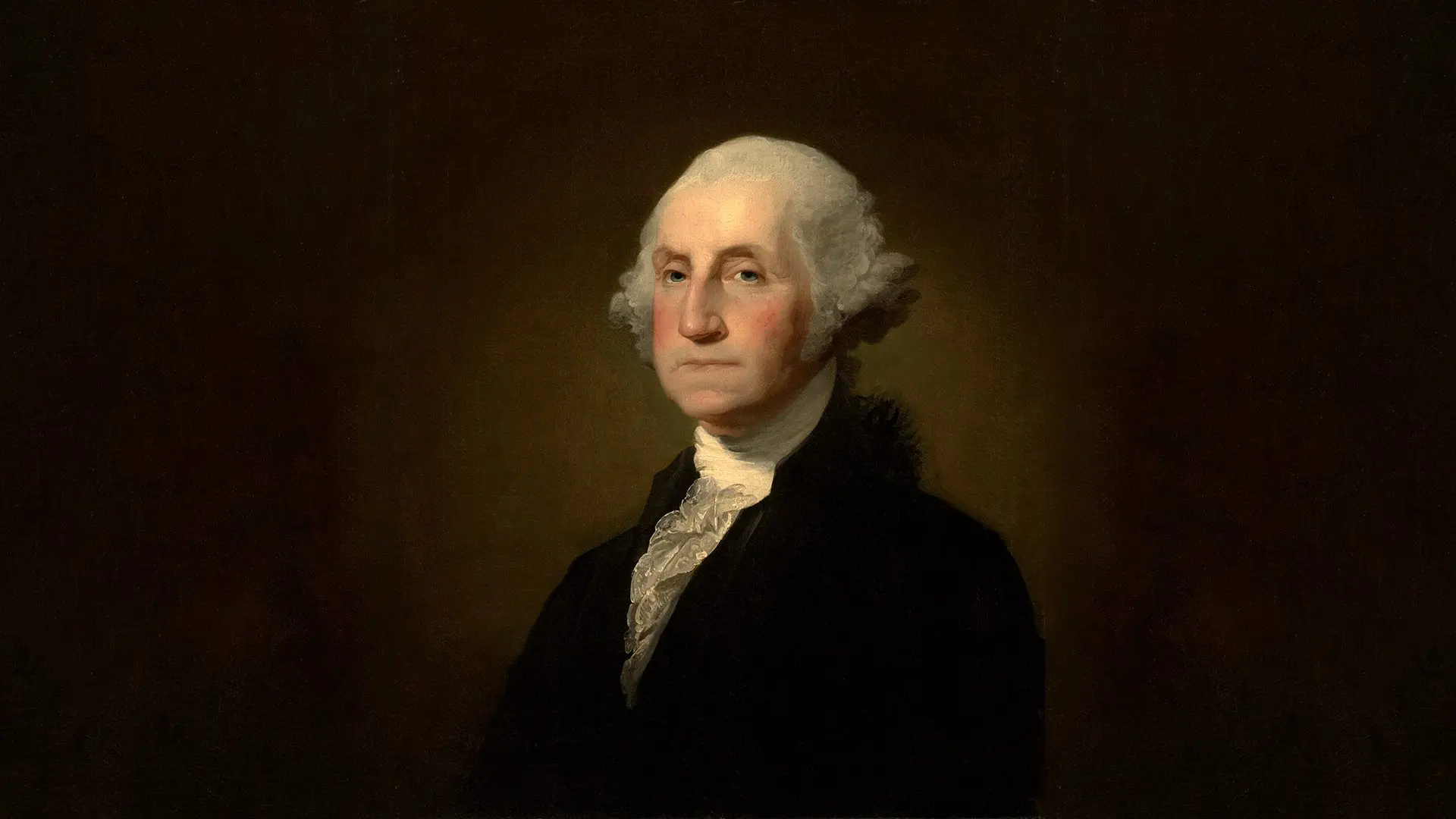

Other powers included acting as the Commander in Chief of the armed forces and militia when called into service as well as the ability to negotiate treaties with the advice and consent of the Senate and to also appoint and receive ambassadors and consuls. Supreme Court justices as well as constitutional scholars have deemed this the concept of the “Unitary Executive,” and the scope of such authority is the subject to this day of judicial review and statements as to “what the law is.” On the Supreme Court docket as I write this, we await decisions on the President’s authority to fire executive branch members, mold agencies to conform to his agenda, fund foreign interests, and even fire Federal Reserve Board members. Nonetheless, the power is deemed significant, and the historical gloss of the powers of this Office has been forged by the exercise of Presidential authority throughout our history—which acts have been considered as precedent for many actions, including introducing armed forces into hostilities short of all-out war and having the primary responsibility for our foreign relations. President George Washington threw down that gauntlet.

When sworn in as President, George Washington was presiding over an office that was a clean slate, and he was charged with stewardship over a new nation thrust onto a world stage that was dangerous. Europe had been at war with itself for centuries, and colonialism and religion and everything else embroiled its countries in this constant vortex of blood and treasure being shed and expended as a matter of course. France had been an important force and ally in our achieving of independence, and we entered a Treaty with France in 1778, which was defensive in nature. The Proclamation discussed below was seen as a betrayal of our debt of loyalty to France by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and, in contrast, a potential quagmire detrimental to the commercial interests of our nation by the Hamiltonian Federalists. More on that below. These divisions and political factionalism became intense, as Jefferson ultimately resigned his position as Secretary of State in late 1793 to fortify his political party’s agenda and influence in opposition to the Federalists.

By early 1793, France became embroiled in a war with Great Britain after the French Revolution. Britain’s declaration of war and the reasons therefor are beyond this piece; however, the situation then existing in Europe placed the new President in a difficult position as he was pulled in two different directions. Jefferson and the political party he led (Democrat-Republicans) and the Federalists under Hamilton were divided by political and economic goals. Hamilton favored ties with Britain, a valuable trading partner, and Jefferson favored the Enlightenment-fueled goals of the French Revolution and deeply felt that we owed this allegiance to our previous ally. Jefferson urged intervention. Hamilton, Washington’s protégé and ally, favored neutrality and trade for a nation not ready for such a projection of power.

The new President was torn in these directions, and his decision, discussed below, would cause debate and derision in Congress and disunity of public opinion. What emerged was the forging of the foreign affairs authority of the Executive that has, in large part, been validated throughout our constitutional history.

PRESIDENT WASHINGTON ISSUES A PROCLAMATION OF NEUTRALITY ON APRIL 22ND 1793

This action of the President was not only a declaration of a foreign policy of neutrality and peace, but also the taking of constitutional ground in the new nation. It reflected Washington’s reluctance to engage in foreign entanglements with little benefit to the United States as well as firing a warning shot to any citizen who would violate this Proclamation and assist either of the warring sides. He sought stability and not chaos. It is reproduced here:

“Whereas it appears that a state of war exists between Austria, Prussia, Sardinia, Great-Britain, and the United Netherlands, of the one part, and France on the other, and the duty and interest of the United States require, that they should with sincerity and good faith adopt and pursue a conduct friendly and impartial toward the belligerent powers:

I have therefore thought fit by these presents to declare the disposition of the United States to observe the conduct aforesaid towards those powers respectively; and to exhort and warn the citizens of the United States carefully to avoid all acts and proceedings whatsover, which may in any manner tend to contravene such disposition.

And I do hereby also make known that whosoever of the citizens of the United States shall render himself liable to punishment or forfeiture under the law of nations, by committing, aiding or abetting hostilities against any of the said powers, or by carrying to any of them those articles, which are deemed contraband by the modern usage of nations, will not receive the protection of the United States, against such punishment or forfeiture: and further, that I have given instructions to those officers, to whom it belongs, to cause prosecutions to be instituted against all persons, who shall, within the cognizance of the courts of the United States, violate the Law of Nations, with respect to the powers at war, or any of them.”

HAMILTON RALLIES TO WASHINGTON’S DEFENSE IN A SERIES OF ARTICLES WRITTEN UNDER THE NAME “PACIFICUS”—IN PACIFICUS I PUBLISHED ON 29 JUNE 1793 IN PHILADELPHIA, AND IN A FURTHER SERIES HE MADE HIS ARTICLE II CASE

In the first of a series of articles, Hamilton, writing as “Pacificus,” a practice that one must assume was common at the time, laid out the political and legal objections to Washington’s Proclamation voiced by his own Secretary of State as well as Congress, in addition to certain segments of the public:

“That the Proclamation was without authority;

That it was contrary to our treaties with France;

That it was contrary to the gratitude, which is due from this to that country; for the succors rendered us in our own Revolution;

That it was out of time & unnecessary”

Hamilton went right to Article II’s vesting authority in a rebuke of these contentions as well as a logical reading of the separation of powers and the policies set forth and implied in the relevant clauses in Article II. He concluded that the foreign affairs authority of the President included decisions regarding neutrality and related issues independent of Congress’ authority to declare war as set forth in the text of Article I.

“A correct and well-informed mind will discern at once that it can belong neither to the legislative nor judicial department and, of course, must belong to the executive.

The legislative department is not the organ of intercourse between the United States and foreign nations. It is charged neither with making nor interpreting treaties. It is therefore not naturally that organ of the government which is to pronounce the existing condition of the nation, with regard to foreign powers, or to admonish the citizens of their obligations and duties as founded upon that condition of things. Still less is it charged with enforcing the execution and observance of these obligations and those duties.

It is equally obvious that the act in question is foreign to the judiciary department of the government. The province of that department is to decide litigations in particular cases. It is indeed charged with the interpretation of treaties; but it exercises this function only in the litigated cases; that is where contending parties bring before it a specific controversy. It has no concern with pronouncing upon the external political relations of treaties between government and government.

It must then of necessity belong to the executive department to exercise the function in question—when a proper case for the exercise of it occurs.

It appears to be connected with that department in various capacities, as the organ of intercourse between the nation and foreign nations—as the interpreter of the national treaties in those cases in which the judiciary is not competent, that is in the cases between government and government—as that power, which is charged with the execution of the laws, of which treaties form a part—as that power which is charged with the command and application of the public force.

This view of the subject is so natural and obvious—so analogous to general theory and practice—that no doubt can be entertained of its justness, unless such doubt can be deduced from particular provisions of the Constitution of the United States.

Let us see then if cause for such doubt is to be found in that constitution.

The second Article of the Constitution of the United States, section 1st, established this general proposition, that ‘The executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America’.”

Hamilton concluded,

“…While therefore the Legislature can alone declare war, can alone actually transfer the nation from a state of Peace to a state of war—it belongs to the ‘Executive Power,’ to do whatever else the laws of Nations cooperating with the Treaties of the Country enjoin, in the intercourse of the UStates with foreign Powers.”

IN RESPONSE, JEFFERSON PERSUADES HIS ALLY JAMES MADISON TO RESPOND AS “HELVIDIUS” IN A SIMILAR SERIES OF ARTICLES IN WHAT IS KNOWN AS THE PACIFICUS-HELVIDIUS DEBATES

James Madison believed that war powers as well as recognitions of neutrality are intertwined and that Congress had the sole power to declare war and make treaties, which he strongly urged were legislative functions. He stated, “…To say then that the power of making treaties, which are confessedly laws, belongs naturally to the department which is to execute laws is to say that the executive department naturally includes a legislative power. In theory this is an absurdity—in practice a tyranny.” He further rebuked any notion that the Constitution delegated anywhere in its text a power in the President to solely make war or peace, for that matter.

History debates the topic, but the bulk of scholarly history and judicial precedent seems to have vindicated Hamilton’s interpretation.

WASHINGTON’S FAILING HEALTH AND THE DEVELOPING POLITICAL FACTIONALISM IN THE NEW NATION CAUSED HIM TO BID FAREWELL TO THE AMERICAN PUBLIC IN 1796

President George Washington, in his Farewell Address of September 19th, 1796, originally published in Philadelphia’s Daily American Advertiser as a letter to the American people, included this missive regarding foreign entanglements, the philosophy of which led to his earlier Proclamation of Neutrality.

“The great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible. So far as we have already formed engagements, let them be fulfilled with perfect good faith. Here let us stop. Europe has a set of primary interests which to us have none; or a very remote relation. Hence she must be engaged in frequent controversies, the causes of which are essentially foreign to our concerns. Hence, therefore, it must be unwise in us to implicate ourselves by artificial ties in the ordinary vicissitudes of her politics, or the ordinary combinations and collisions of her friendships or enmities.

Our detached and distant situation invites and enables us to pursue a different course. If we remain one people under an efficient government. The period is not far off when we may defy material injury from external annoyance; when we may take such an attitude as will cause the neutrality we may at any time resolve upon to be scrupulously respected; when belligerent nations, under the impossibility of making acquisitions upon us, will not lightly hazard the giving us provocation; when we may choose peace or war, as our interest, guided by justice, shall counsel.

Why forego the advantages of so peculiar a situation? Why quit our own to stand upon foreign ground? Why, by interweaving our destiny with that of any part of Europe, entangle our peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, rivalship, interest, humor or caprice?”

Three years after his Proclamation, he still felt compelled to press home the wisdom of his decision and the timing of it. His logic is no less compelling today as we debate the foreign policy of the nation. The Neutrality Act of 1794 was passed by Congress, validating this executive authority and codified Washington’s Proclamation in large measure, and actually gave the executive authority to enforce its provisions and to keep the nascent union out of foreign entanglements such as those occurring in Europe. It is widely accepted that Washington’s bold and moral stance for peace and prosperity set the tone for American foreign policy and the powers of the Presidency to shape and influence it.

CONCLUSION

I commend to all a reading of Washington’s full Farewell Address, written originally by Madison but finished by Hamilton. It sets forth a condemnation of political factionalism and cautions against foreign entanglements for which there is little national interest or benefit. Although history has established the necessity of joining issue on foreign battlefields and the projection of power where indicated in the national interest, the basic policies enshrined in these words are no less relevant today. Washington also warned against the type of political factionalism that dominates in the modern era. Common ground is a distant goal. Perhaps we can find some before it is too late. I fear it already is.

Mike Imprevento

February 16th, 2026